Cross Fell

Cross Fell is the highest peak in the Pennines, and last weekend, Sam and I decided to climb it (along with a couple of other lesser peaks). It's also on the Trail 100, of which we've climbed 6 or 7. From what I've read, most people climb Cross Fell from the Eden Valley in the west, usually from the tiny village of Kirkland, straight up the side of the fell. While not, I imagine, without its charms, Sam and I were looking for something a little more remote, and so decided to climb up to Cross Fell from Garrigill in the east, up the headwaters of the South Tyne and summiting Cross Fell as we looped around the head of the Tees.

We had originally planned to do the walk in two days, but found after rising early that we'd made too good time, so we headed right back down. 32 kilometers is probably a bit far to ask most people to walk in a day, so unless you're feeling particularly gluttonous for punishment, overnighting at Greg's Hut is probably the better plan.

As of writing, Greg's Hut is closed due to COVID-19. Bear that in mind as you make your plans.

Garrigill

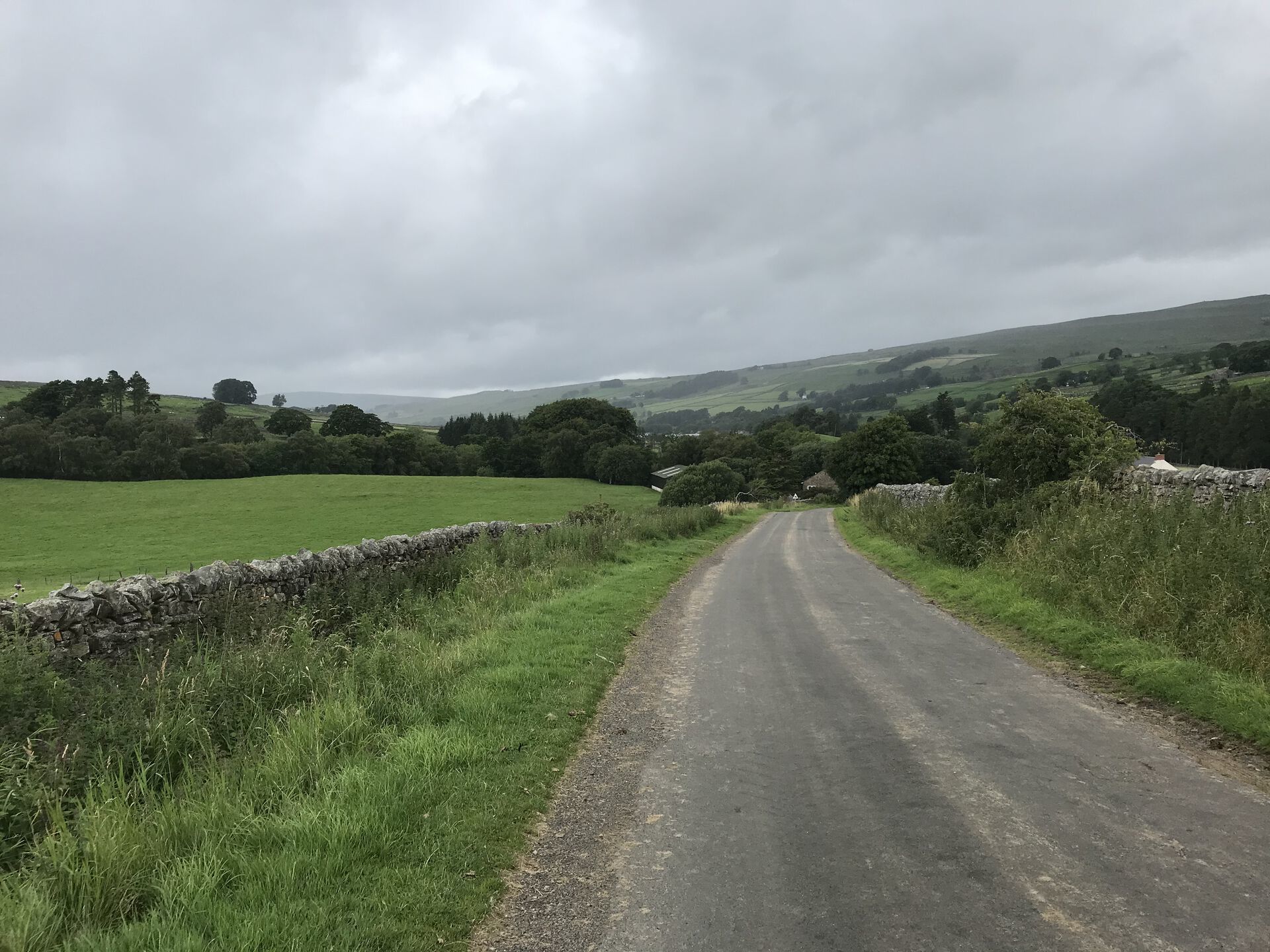

We parked our car in the village of Garrigill, some 4 miles or so southwest of Alston. Plenty of roadside parking; we posted the little Clio up outside of the village hall, where we found some very clean public toilets.

The beginning of the walk took us up a road alongside the River South Tyne. South Tynedale is nice and quiet, with only a couple of farms along the road. We met a couple of fell runners coming out of the hills, and were passed at one point by a tractor, but otherwise it was quiet walking.

After about 3.5 kilometers, we came to the end of the road. We'd made a bit of elevation by this point, and while the clouds were low, we could see a good deal of the valley behind us. From here we followed a dirt track further up out of the dale and into the moor: easy, gradual walking. Crossed a rather new-looking concrete bridge over the South Tyne and kept climbing. Made good time through here.

The farmer seemed to have been doing some renovations on his land—we saw lots of freshly paved road, tons of new fencing, and a whole plantation of young trees on the way up.

In the upper reaches of the dale, we started to come across the first of many signs of lead mining in the area. Up on the right, we spotted a couple of old building foundations among huge slag piles. The OS map for the area shows plenty of disused shafts, shake holes, and a couple of hushes, which I'll go into in a bit.

Near the top of the dale we came to a little monument to the source of the South Tyne. As the road was levelling out a bit, we stopped and had a candy bar.

Moor House - Upper Teesdale National Nature Reserve

Past here, the road sort of meanders around the southwest flank of the big round Tynehead Fell, passing a ruined building and an old sheepfold along the way. We soon came across an abandoned lead mine complex standing along the edge of the River Tees (which, frankly, seemed to jump out of nowhere (the Tees)). A whole bunch of rubble and a bit of wall still standing marks the spot. We then passed through a gate here into Moor House - Upper Teesdale National Nature Reserve and joined the picturesque Trout Beck, heading southwest.

I don't suspect there's a ton of trout up here on the moor, somehow.

For a little ways, the path along Trout Beck is actually paved—I think to serve Moor House (where Sam says someone actually lives, but I'm not sure), but near a weir the paved road cuts off across Trout Beck and continues past a locked gate. We continued up the little path alongside the beck.

Just about every map you'll look at shows Moor House featuring a public telephone. Sam says this is exceedingly strange.

Here and there it looks like the path has succumbed to a bit of subsidence, but generally the trail was remarkably easy to follow. Not much climbing through here either, which was nice. We stopped for lunch on a bit of a little shoal in the river. In heavier weather it might have even been an island. It feels really isolated up there, along the little stream. The water gurgled in just the right way as to make it sound like voices off in the distance. A little unsettling.

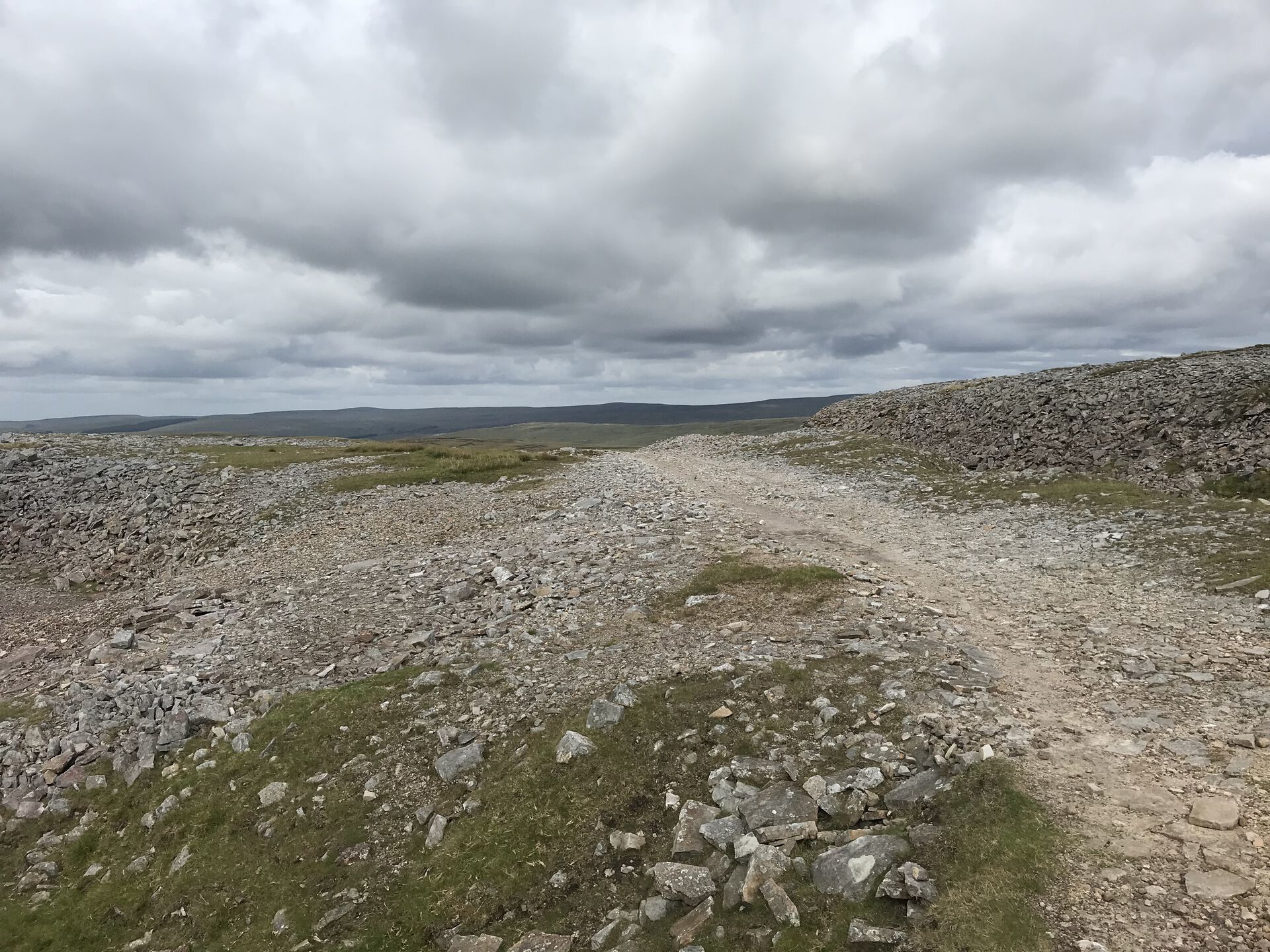

Continuing on for a little while, we eventually reached the top of Trout Beck and had to start climbing in earnest. Here we came across a a ton of loose soil and sand, and then, more impressively, a series of hushings on the climb up to Great Dun Fell.

A couple words on hushings from Sam

Also called hydraulic mining, this is a method of exposing and/or exploiting mineral veins that using great torrents of water. There would have been a tank or dam at the top and a sluice gate, which when opened would have blown the soil away to (hopefully) reveal the mineral beneath. It was first used in Britain by Romans (although in Wales for gold mining) but in the context of Dunfell Hush, the technique was employed by the Georgians to uncover lead. Dunfell Hush is notable because of how massive it is — about 100 feet deep apparently. It’s hard to imagine what the land must have looked like a couple of hundred years ago before we carved a big chunk out of it.

As we climbed up alongside the hushing, we caught our first glimpses of the radar station atop Great Dun Fell. It looked pretty small at first but the size of the radome quickly became apparent as we approached.

We met up with the paved road leading up to the radar station and then cut north, joining the Pennine Way up along the shoulder of the fell, crossing the very top of Dunfell Hush.

Great Dun Fell

In time we crested the side of Great Dun Fell and spotted Little Dun Fell rising beyond it. Great Dun Fell, as it turns out, is the second highest peak in the Pennines; and Little Dun Fell isn't actually that much littler, at 842 meters to Great Dun Fell's 848.

As we came round the flank of the mountain, we also caught our first glimpses of the Lake District across the Eden Valley. It was a bit of a hazy day, so we didn't get much more than the many-layered outlines of the fells—but that was enough.

Little Dun Fell

Heading down Great Dun Fell, the grassy path was soon replaced with huge flagstones, making the going easy once more. The climb up to Little Dun Fell only consists of 80 meters of vertical or so: short work. A big pile of rocks atop Little Dun Fell marks the summit; but Cross Fell was just across the way, so we didn't stop.

The north face of Little Dun Fell was littered with rocks and smaller boulders; couldn't figure out why, or how they'd got there. Just north of the summit, there was a little shelter cobbled together out of stones; not sure why anyone would stop here, though, when Cross Fell is just across the way. So down we went along more flagstones, through a bit of boggy terrain in the saddle, crossing an east-west bridleway, and up the other side.

Cross Fell

The climb up to Cross Fell had us cross a field of those small boulders, so a bit of rock-hopping was in order. Shortly we crested the steepest part and came across the tallest cairn I've ever seen. Though it looked expertly balanced, I couldn't get up the nerve to have my picture taken with it, for fear of it tumbling over onto me. A little ways onward and we came to the summit of Cross Fell.

Not much here: a trig point and a drystone shelter in the shape of a cross, so you can get out of the wind no matter which way it's blowing. More great views of the Lakes. On the way up, we saw what looked like a series of cairns heading off eastward, but the OS map doesn't show any trails off that way, so I'm not sure what the story is there.

At this point, we decided that if we walked down to Greg's Hut, we'd wind up sitting around for 4 or 5 hours before the sun went down and we'd be able to get to sleep, and both of us were peppy enough to walk down, but tired enough to want our own bed. So, loaded up with food, sleeping bags, tent, stove, and the rest, we started the ~13 km walk back down to Garrigill.

A short trek across a boggy slope took us down to a junction with the A Pennine Journey trail, where we headed off east. A ton more shake holes along the rocky path here. I guess this must have served as an old road for all of the mines along here.

Greg's Hut

By and by, without much ado, we came to Greg's Hut. A little gate across the road announced our arrival. Greg's Hut was apparently built sometime in the 1800s as a blacksmith's shop and was also used as a field house for miners from Garrigill or the Eden Valley. More info at the Mountain Bothies Association.

Not wanting to linger at a closed bothy, we scarfed a couple of candy bars and continued on our way. Past a number of very deep shake holes startlingly close to the trail, I was glad of the clear weather. Wouldn't want to stumble into one of them in the fog.

A couple words on shake holes from Sam

You might know them as sink holes but in the North Pennines they’re called shake holes. I always connected the dots between the amount of mining in the North Pennines and the uncountable number of shake holes but, alas, I was mistaken. The North Pennines, geologically speaking, is made up largely of carboniferous rocks. That means they’re limestoney and soft. And unless you’ve been living in a bubble, you’ll know England is a wet place. Water erodes soft rocks. Couple of million years later and you’ve got shake holes.

The walk onward from here was pretty uneventful. The huge moor off to the north of us was nice to look at, but by this point, we'd been staring at moorland all day and our feet were aching. The rocky path by and by broke down into a yellow, gravelly one—slightly easier on the feet but by no means easy. Spare a thought for the miners walking this trail weekly in whatever passed for rugged footwear 150 years ago.

Alston Moor

Eventually we started descending the long side of Alston Moor on the walk back down into Garrigill. A Mitsubishi pickup came trundling up the road at one point; we waved weakly at the driver and his pint-sized daughter in the passenger seat. Further along, we came across a man assembling a drystone wall alongside the road. What we could see of the completed wall was absolutely stunning. Remind me to take up drystone walling at some point.

The road grew reasonably steep at one point, but then crossed through a little stand of trees and ended in someone's drive. From there it was a short walk through the town (and a bereft look over the shoulder at the shuttered up George and Dragon pub) before arriving back at Lil' Red, parked up by the village hall.

Previous

The good, the bad, & the confusing JavaScript

My entry in the canon of explanation for why JS developers always seem so tired