A Pennine Journey

by A. Wainwright

Published 1986 213 pagesThe Story of a Long Walk in 1938

I’ve walked parts of Wainwright’s Pennine Journey and found it a little rough around the edges — though not necessarily in a bad way. There are sections that follow greenways and high moorland tracks like the most well-trod of the long distance trails here in England; but there are long tracts that meander across fields and over stone walls and through farm courtyards in a way that I think Wainwright might have liked.

Wainwright’s original journey, however, followed very little of the modern signposted route; in 1938 the relatively infrequent motor traffic down what are now designated B-roads meant that he could walk along the roads and lanes and see almost no one. At one point he walks five miles up the road from Alston to Hartside Cross, a voyage no one would dare to undertake by foot these days for danger of being plastered by a BMW X9 operated by a wealthy family from Coventry out on their bank holiday weekend jollies.

A Pennine Journey (the book, not the trail) is a book of two faces.

On the one hand, Wainwright writes loftily of the freedom of the hills, dales, and wideopen lonely places in the north of England; he brings the reader with him into towns that have scarcely changed in hundreds of years, stone walls and flagstone roofs and modest kitchens with a little coal in the grate.

He makes his opinion well-known: Blanchland is out of a fairy-tale; Weardale is industrially depressing; Wharfedale is a secret beauty; the Eden Valley sucks. He writes at length and with unmitigated wonder of Hadrian’s Wall (although inexplicably totally omits any mention of Sycamore Gap (RIP In Peace)).

This tendency of forming a strong opinion of what is basically just grass and stone and tree is what has made him a national treasure (and an MBE). It’s charming and captivating and breeds a sense of romance into the country.

Oh, how can I put into words the joys of a walkover country such as this; the scene that delight the eyes, the blessed piece of mind, the sheer exuberance which fills your soul as you tread the firm turf? This is something to be lived, not read about. On these breezy heights, a transformation is wondrously rot within you. Your thoughts are simple, in tune with your surroundings; the complicated problems you brought with you from the town or smooth away. Up here, you are near to your Creator; you are conscious of the infinite; you gain new perspectives; thoughts run in new strange channels; there are stirrings in your soul which are quite beyond the power of my pen to describe.

On the other hand. He is a little bit too free with that opinion when it comes to women. And his journey brings him into contact with all sorts of women: his MO is basically to rock up as the sun is setting and find someone to take him in for the night. Usually this is a private home (but sometimes an inn) where a woman looks after occasional boarders, and always does A.W. have something to say about these women.

Usually it’s condescending. Usually it reads like something from r/menwritingwomen. Sometimes it’s outright offensive. He flirts with all of the younger ones, despite having a wife of seven years and a son back home; he passes judgment on the elder.

And he holds a pretty high opinion of himself; I quite suspect that he was a miserable person to be around (which is lucky, because he liked to walk on his own). I’m conscious that A.W. wrote this when he was young (but not that young); he may have let judiciousness get the better of his free opinions in his older age. But I’m also conscious that his wife left him after suspecting him of infidelity, and for his lofty pronouncements about “The man has not been born, who does not want a son to follow him”, he left nothing to his son when he died.

So! The scales have fallen from my eyes. Will I still read his Pictorial Guides to the Lakeland Fells in the idle moments between fell runs? Uh yeah I will. Am I going to read another one of his narrative walks? Uh probably not.

Stray observations

- Wainwright stops at the Kirk Inn in Romaldkirk and his description heavily implies that it’s haunted or cursed or something; that despite the solicitousness of the widow who runs the joint there’s a shabby sense of bereft laid over the place like a cloak. He speculates that it will very soon go out of business but: it didn’t! It’s still around. Sam and I visited last weekend and found that the curse still lays upon the place: it is dark and cluttered even on a sunny day, serves only a single beer from a brewery I have never heard of, and remains perennially empty even on a Friday evening, while the (larger, more upscale) pub across the street is fully-booked. The solicitous proprietor remains: the pub does not take cards but does take a promise to return within the hour with a crisp polymer tenner.

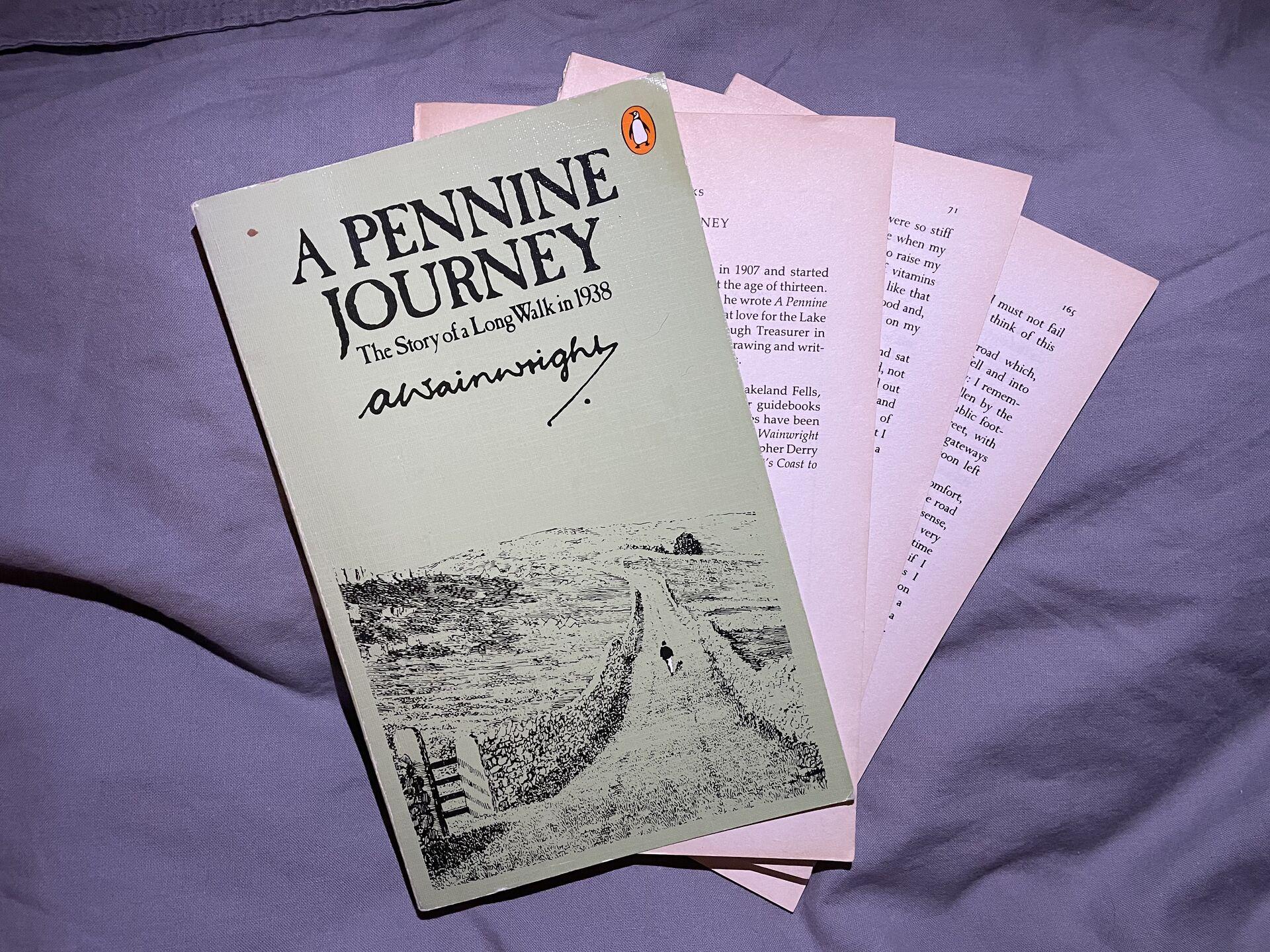

- I got the book off World of Books and when it arrived it was battered but whole; by the time I finished it went the way of A.W.’s shoes, by which I mean the adhesive had totally perished and the whole thing came pretty much totally apart.

Next