Life and Fate

by Vasily Grossman

Published 1959 864 pages

Life and Fate, Grossman’s epic of life under totalitarian rule at the time of the Battle of Stalingrad, pulls no punches in depicting the human soul under totalitarian rule.

Most of the story contends with the Shaposhnikov family and their relationships. At the very core of this story are Lyudmila Nikolaevna Shaposhnikov and her husband Viktor Shtrum; Viktor is grappling with his work in nuclear physics, his relationships with fellow academics, and his inability to reconcile his dissident belief with his State science career; Lyudmila is struggling to come to term with the death of her son from her first marriage (her first husband, a staunch Bolshevik, is in prison). Shtrum is struggling to work out a formula to reconcile the results of experiments his lab is undertaking in atomic physics; he's frustrated by his inability to voice his dissident thoughts about the State and by conflicting reports of informers among his friends. One night, after a polemic against the State, however, he has a breakthrough, and his research takes off—however, with his star rising, his colleagues begin to plot his downfall. Only a call from Stalin himself saves him from total ruin—but once again in power, he waffles and submits to the will of the Party.

Shtrum's sister-in-law Yevgenia Nikolaevna, enters the story relatively early as well; she’s also in a new relationship following a divorce from her first husband. While she hasn’t quite decided whether she really likes her new beau Novikov, the shrewd commander of a tank corps on the Stalingrad front, he thinks of herpretty much constantly at the front lines. Novikov’s corps is overseen by a pair of party hacks, Getmanov and Nyeudobnov; the tension between their Party-line-toeing and Novikov’s more practical battle-sense colours much of Grossman’s commentary on the nature of war.

Grossman, a wartime correspondant who experienced Stalingrad firsthand, treats war as wholly alienating: from society, from cultural rules, and—mostly importantly—from the State. While war is a crucible of pain, it's also when man is at his most free, most capable of exercising the fundamental kindness that forms the "kernel" of human nature. Grekov, a soldier in a besieged house held only by the grit of his men, and knowing that a German strike is forthcoming, orders one of the younger soldiers away with the radio operator, with whom the younger solider is in love. Later on, two soldiers shelter from an artillery barrage in a crater, holding hands through the chaos—only to realise in the aftermath that one is Russian and one German. They slink off without sharing a word. And in the cells & interrogation rooms of the Lubyanka, Krymov—Yevgenia's erstwhile husband—holds out hope in his love for Yevgenia.

Human history is not the battle of good struggling to overcome evil. It is a battle fought by a great evil struggling to crush a kernel of human kindness. But if what is human in human beings has not been destroyed even now, then evil will never conquer.

Under totalitarian rule, however, humans are easily crushed and manipulated; there are long passages about the shifting of blame and countless instances of people trying to absolve themselves—“you didn’t hear it from me,” etc. We got this sort of thing a lot in the Chernobyl miniseries, too. When Lyudmila visits hospital where her son died, for instance, she finds that all of the staff want to meet and speak with her—not to recount how Tolya spent his final days, but to seek absolution, the assurance that his death was not their fault. Lyudmila takes this as a matter of course.

The shifting an application of blame is a recurring motif as well. The director of a power station in Stalingrad, tired of waiting around at the bombed-out shell of the station, leaves to tend to the birth of his grandson; when the siege is lifted the day afterwards, he's accused of abandoning his post and is reassigned to Siberia. Novikov, leading a tank charge during the encirclement of the German Sixth Army, holds back for four minutes to allow the artillery to finish their barrage: he's concerned that his men could be inadvertently caught up. Once he strikes, however, he quickly takes all objectives with minimal losses. The Party commissar with him beams in delight at the wild success of the offensive, and then drafts up a denunciation against Novikov for the delay, seeking to curry favor by outing enemies of the State.

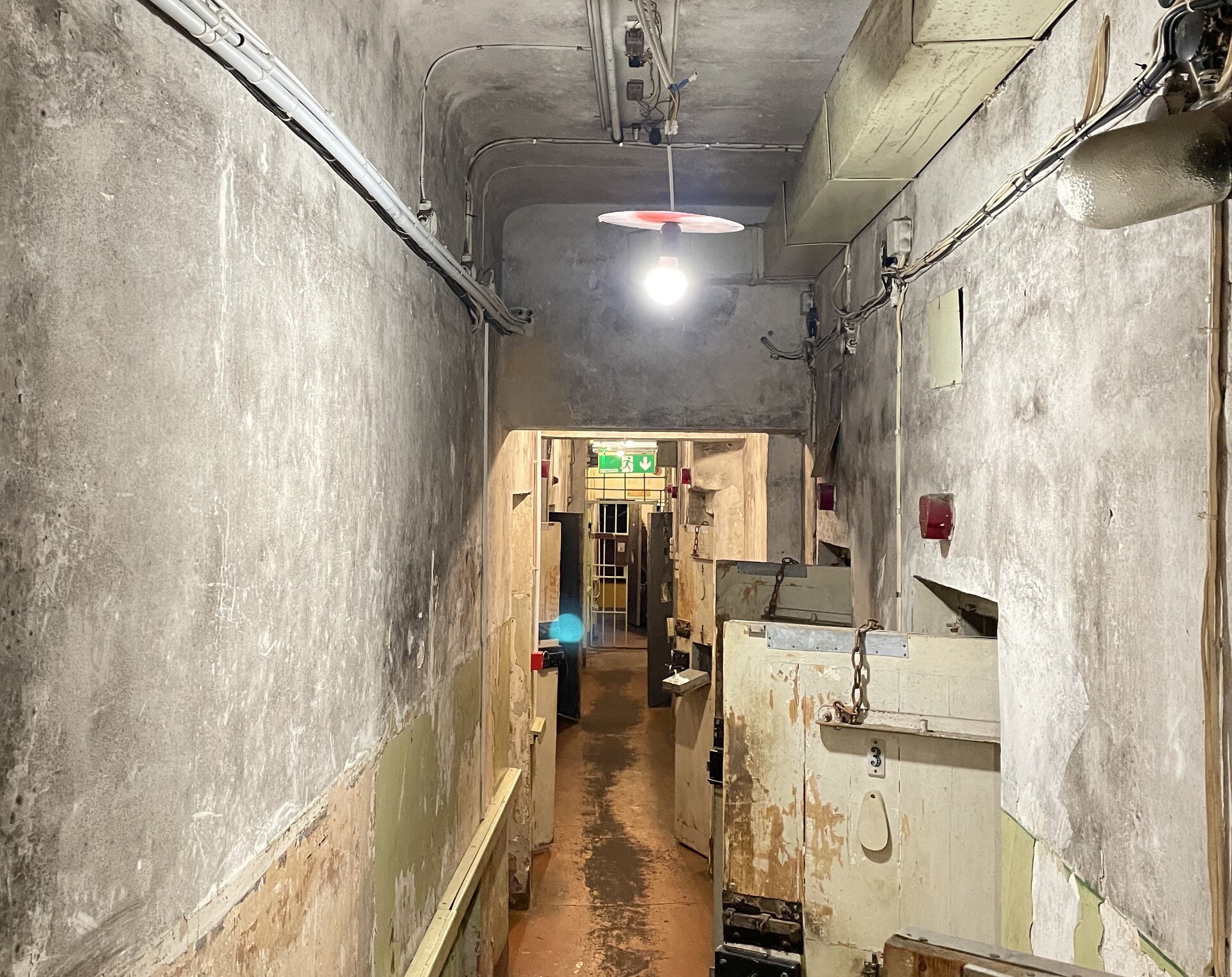

Some of the most harrowing scenes, however, are saved for the prison camps. The camps are run by criminals; political prisoners are second-class citizens, made to do the dirty work. Party fervor lives on, here, however: two resolved Bolsheviks fight for their belief in the State and come out no better for it.

The most horribles scenes, however, take place on a train arriving at a German death camp. Sofya Levinton, a Jewish doctor, adopts a young boy in the train car, and elects to stay with him when the Germans call for doctors. As the healthy men and educated workers are are sent to the work camp and the rest directed to the gas chambers, Grossman leaves us with probably the most powerful paragraph in the whole book:

How can one convey the feelings of a man pressing his wife's hand for the last time? How can one describe that last, quick look at a beloved face? Yes, and how can a man live with the merciless memory of how, during the silence of parting, he blinked for a moment to hide the crude joy he felt at having managed to save his life? How can he ever bury the memory of his wife handing him a packet containing her wedding ring, a rusk and some sugar-lumps? How can he continue to exist, seeing the glow in the sky flaring up with renewed strength? Now the hands he had kissed must be burning, now the eyes that had admired hm, now the hair whose smell he could recognize in the darkness, now his children, his wife, his mother. How can he ask for a place in the barracks nearer the stove? How can he hold out his bowl for a litre of grey swill? How can he repair the torn sole of his boot? How can he wield a crowbar? How can he drink? How can he breathe? With the screams of his mother and children in his ears?

Next