The Yearling

by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings

Published 1938 428 pages

The Yearling is the perfect example of a certain kind of story written in the first half of the twentieth century that got turned into a hundred million movies starring Gregory Peck. It’s the quintessential example of a bildungsroman set in the American south. It’s got man vs. wild. It’s got boy vs. wild. It’s got boy + wild. It’s got fathers and sons. It’s got grimy scallywag types. It’s got language you can sink your teeth into. It’s got a character arc that you can see the whole thing right from the very beginning. It’s got no black people. It’s got absolutely zero tension. This is the America that they want to make great again.

The Yearling is the story of Penny Baxter, a pioneer in the Central Florida backwoods (specifically around Ocala) in the years after the American Civil War. The story is told from the perspective of his son, Jody, who is the eponymous yearling, over the course of a single year as Jody grows from a boy to a young man. Penny and Jody navigate difficult relationships with their neighbours, torrential rains, death of close friends, and skirmishes from the wildlife that threaten their existence in the scrub. However, as I say: no tension. Penny is clever and moral and a solution is never far away.

You may have been told that the yearling of the title actually represents a young fawn that Jody adopts midway through the story, and who grows along with him over the course of the year. That’s just a clever rhetorical technique. I won’t spoil anything here but this book was written in 1938 and won the Pulitzer Prize and was adapted for the screen like 8 times, so I think you can see where this story with the fawn goes.

It’s a little trite, and it’s a little predictable, but the world that Rawlings conjures up is so rich you can almost sink your fingers into it. The blackjack oaks and the sand and the split-rail fences and the long beards and the critters. And the food — almost Ghibli-esque in its detail. Tell me you don’t want to sit down to this table:

She ladled food into pans big enough to wash in. The long trenchered table was covered with steam. There were dried cow-peas boiled with white bacon, a haunch of roast venison, a platter of fried squirrel, swamp cabbage, big hominy, biscuits, cornbread, syrup and coffee. A raisin pudding waited at the side of the hearth.

“If I’d of knowed you was comin’,” she said, “I’d of cooked somethin’ fitten. Well, draw up.”

Or this description of killing a deer, which lays forth the brutality of the wild in such few words:

He took his knife from its scabbard and went to the deer and slit its throat. It died with the quiet of a thing to whom death is only one short step beyond a present misery.

Why can’t we write like this anymore?

Stray observations

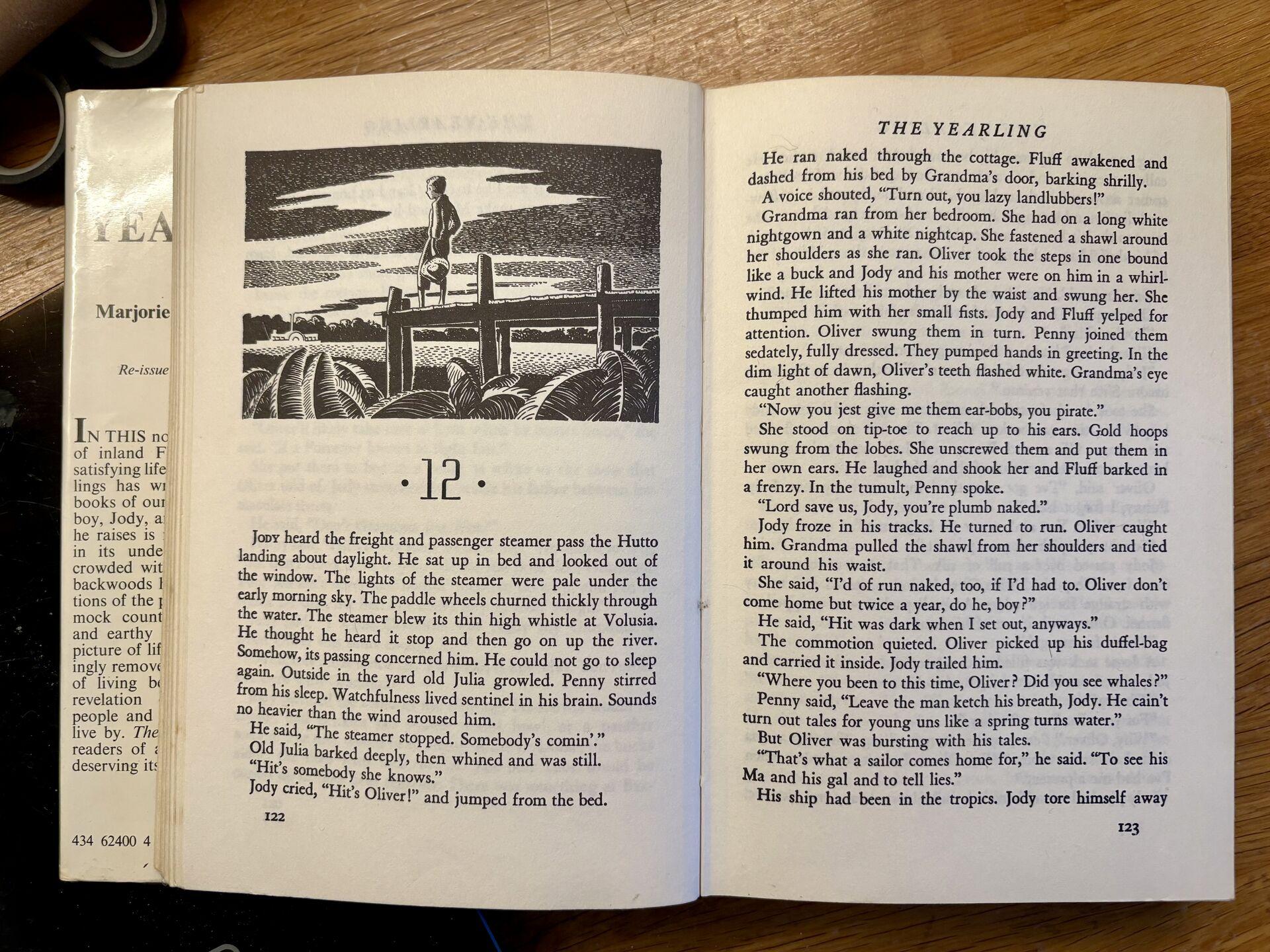

- The edition that I read (pub. Heinemann, 1969), besides having perhaps the perfectly broken spine, also featured these fantastic engraved illustrations at the start of every chapter:

Next

Previous

C2A: Into the Real Netherlands

Riding our bikes below sea level through the heart of the Netherlands.