Week 48

Let me tell you what it looks like just north of Asahikawa, in the summertime.

It's a little before noon on a Sunday. I’m as psychologically present as any 23-year-old is expected to be at a little before noon on a Sunday. I'm sitting very quietly in a car with Oliver. I have the impression that music is playing in the car, but I'm not listening to it, really. The windows are open and the sun is just flooding in, great luminal waves riding through the wind. My left arm is hanging out the open window and the long rubberized strip sealing the power-window sill is cutting into my arm, because it's one of those sharp-edged sills that sticks up from the top rather than sitting flush with the top of the door, which is how Penelope is (and Penelope besides has low and close enough sills that hanging your arm over the edge evokes in you, in a kinda distant way, that intimate wonder that consumes two people whose bodies fit perfectly together, which is a really weird sensation to feel about a car). Every now and again I readjust my arm along the sill and inspect the long pink lines striping the inside of my elbow where the rubber leaves its mark, drawing out a map on my arm. All the hair on my forearm is pressed flat and shivers slightly in the wind. The headrest behind me is really hard and is too far back to lean on comfortably, but my head feels like it weighs a lot more than normal so I crane my neck back anyway, and only after a couple of kilometers of this do I realize that the first job of a good headrest is to prevent whiplash in the case of a rear-end collision, and I pull my head back forward with a sort of weary finality, balancing this weight of bone and liquid and nerve upon my shoulders, like a tall cattail on the tip of your finger.

There are some houses out to the left, low markers out in the long, low fields. They're mostly rice fields so they're all without exception perfectly flat, as opposed to the Okhotsk's rolling, slightly geographically-aberrant fields of potatoes and onions. Fields in the Okhotsk are also scored with wide rows that you can only see down from a certain angle, looking for all the world like swimming lanes or swatches of corduroy. Between the rows of green are long wales of brown, and the whole thing zooms by in a distantly whupping blur from car windows. When you stand on the edges of these big fields and align yourself perpendicularly to the wales everything grants this strange sense of great distance, as if you're looking further than you actually are, losing everything down at the projected vanishing point, though surely the fields don't actually reach that far... right? It's the sort of sight that everyone automatically knows, that everyone can reinhabit through tinted car windows and air conditioning and fuzzed cloth seats and music that they didn't get to choose, an era of long car trips to visit grandparents or cousins living two hours away, maybe in a neighboring state or a couple of counties over. Somehow such trips always span fields like these, no matter where you're going or where you came from. It's just a rule.

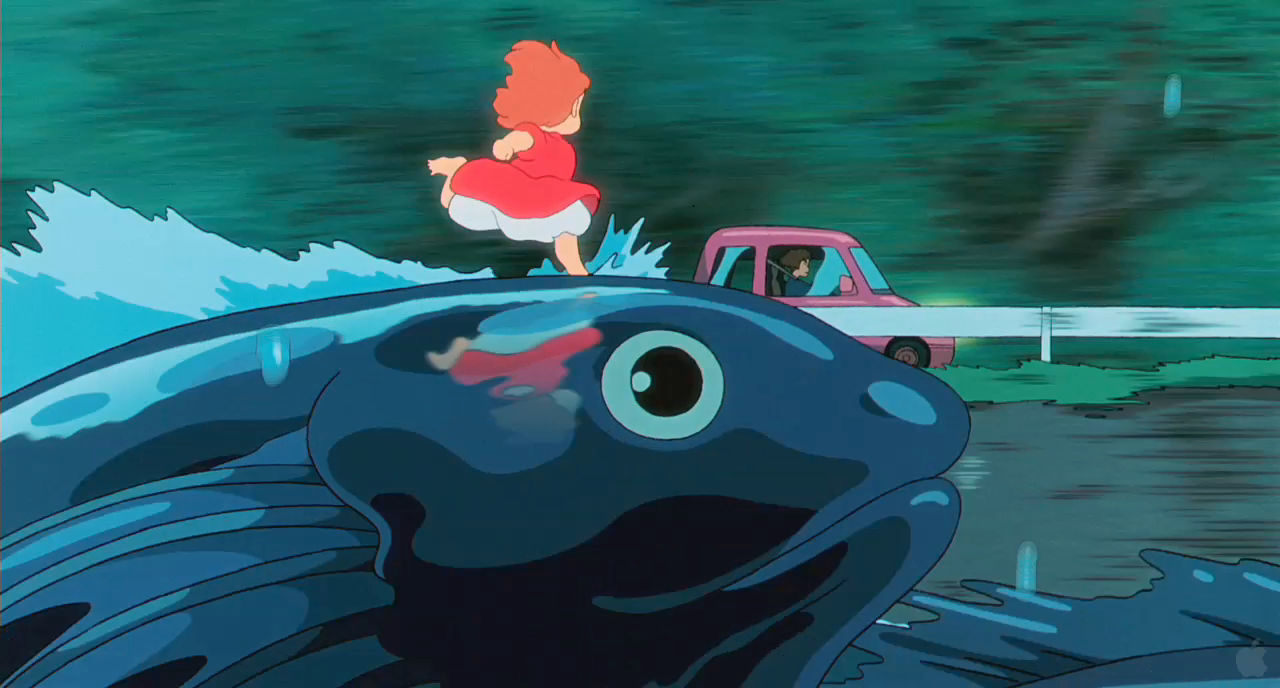

Rice paddies are a lot more densely planted, though, so there's no long lanes between tall healthy-looking stalks -- only a suggestion thereof. And moving as we are at right angles to the field this suggestion becomes even less -- maybe a shallow shimmer of water below, morphing and spasming like an amoeba through the green cover. It looks unreal, like light off water in a Miyazaki movie.

The roofing on most of the houses is patchwork, half blue and half red. I can't tell if the red is rust or paint at this distance, but the impression isn't one of sturdiness or reliability or waterproofing. It looks like temporary solutions (e.g. a quick patch, a tarp thrown over a leak) have become, in intervening years, permanent ones, by some twisting of logic and time. I assume that it's something in that forgotten-to-fix-it snafu that lends the scene its encompassing loneliness; and there are no people to be seen, no workers out in the fields or faces in the windows. We're moving at some 70 kph but things out the window look very still, still.

At one point we cross over the Ishikari River, which this time of year and this far north is little more than a stream, maybe a foot deep in most places and meandering along the dusty riverbed which only a month ago churned with snowmelt. The water glistens through eddies and tumbles down over rocks. From the bridge it looks much too clean, like maybe there's some neo-anti-post-environmentalist group upstream trying to jog back the water cycle by emptying simply unholy amounts of bottled water into the river. The Ishikari River, under the quirked Hokkaido zenith of a Sunday noon, looks distilled.

We briefly cut through the climbing smell of wet rocks. People assume that rocks don't really smell like anything, outside of the ones that we arbitrarily call minerals (e.g. sulfur and sodium and the rest), but rocks under a hot evaporating sun smell healthy, smell like good biology, musty and warm and solid.

Don't ask me how something smells solid. Go smell a rock.

Half of the weirdness of the summer Hokkaido landscape is the ever-presence of emptiness -- the abandoned farms, the wide open fields, the cleared patches of mountainside where logging has left the head of the earth with a little bald spot. The sky is inappreciably big -- no buildings to crowd it out -- and the world is blue from far-off mountains on one side to far-off mountains on the other, a full say like 140 degrees of sky above. Wide and empty. The other half of the weirdness is the juxtaposition of this emptiness with the fullness of nature -- full trees, flowers in full bloom, forest more densely packed than the fur of an otter, flora so thick shoulder-to-shoulder that you're almost certain the forest is violating some biological principle, cheating on its numbers somewhere. And so everywhere you look, Hokkaido's at once full and empty, always in little motion and always totally still, always burning and bursting but always sitting quietly like a giant at rest.

It makes for some pretty arresting visual poetry, a forced negative capability, a withdrawal, a moving-away-from, as though nature is trying to crowd out humans (and in many cases, does):

And at the same time, the vacuum pulls at us, the echoing spaces between the trees, the far air between mountains, which I think is one of the reasons that we all decide to climb mountains in the summer, which when you really think about it, isn’t that weird? That so many of us, from different backgrounds and histories, from everywhere conceivable climate, all decide to climb mountains in the summer, as if there’s nothing else to do here (a false assumption: see this month’s Polestar, p. 19 </shameless promotion>)?

And that's what it looks like just north of Asahikawa, in the summertime.