Nakaaibetsu-yama (中愛別山)

Heads up: I didn’t write this one. This guide is brought to you by my girlfriend Sam, who braved the mountain a couple of weeks ago.

March 4, 2016

Living in Asahikawa is really awesome, mountainly speaking. We’ve got the Daisetsuzan and the mountains out by Ashibetsu, then to the east there’s a load as well. Even closer to home, in Takasu and Asahikawa proper, we have a load of cute wee hills that are a load of fun, like Kitoushi-yama (鬼斗牛山, 379.3 m) . Anyway, so it’s fab. But I don’t have a car. So getting to Asahidake (旭岳, 2291 m) or Tokachidake (十勝岳, 2077 m) or wherever is a total pain in the arse. I have to first get a trail to the nearest town, pray to the Gods that there is a bus that’ll take me to the trailhead but realistically that like never happens. So I’m stuck waiting for other people to be willing to take me along with them on their hiking adventures.

So I was at work one day and because it’s the end of the school year I have nothing of substance to do. I was roaming around on Google Maps wishing I was somewhere I wasn’t, when I realised that the Asahikawa-Kamikawa train line is really close to some mountains. I love to research logistics and stuff like that when I’m bored so I got to ‘work’.

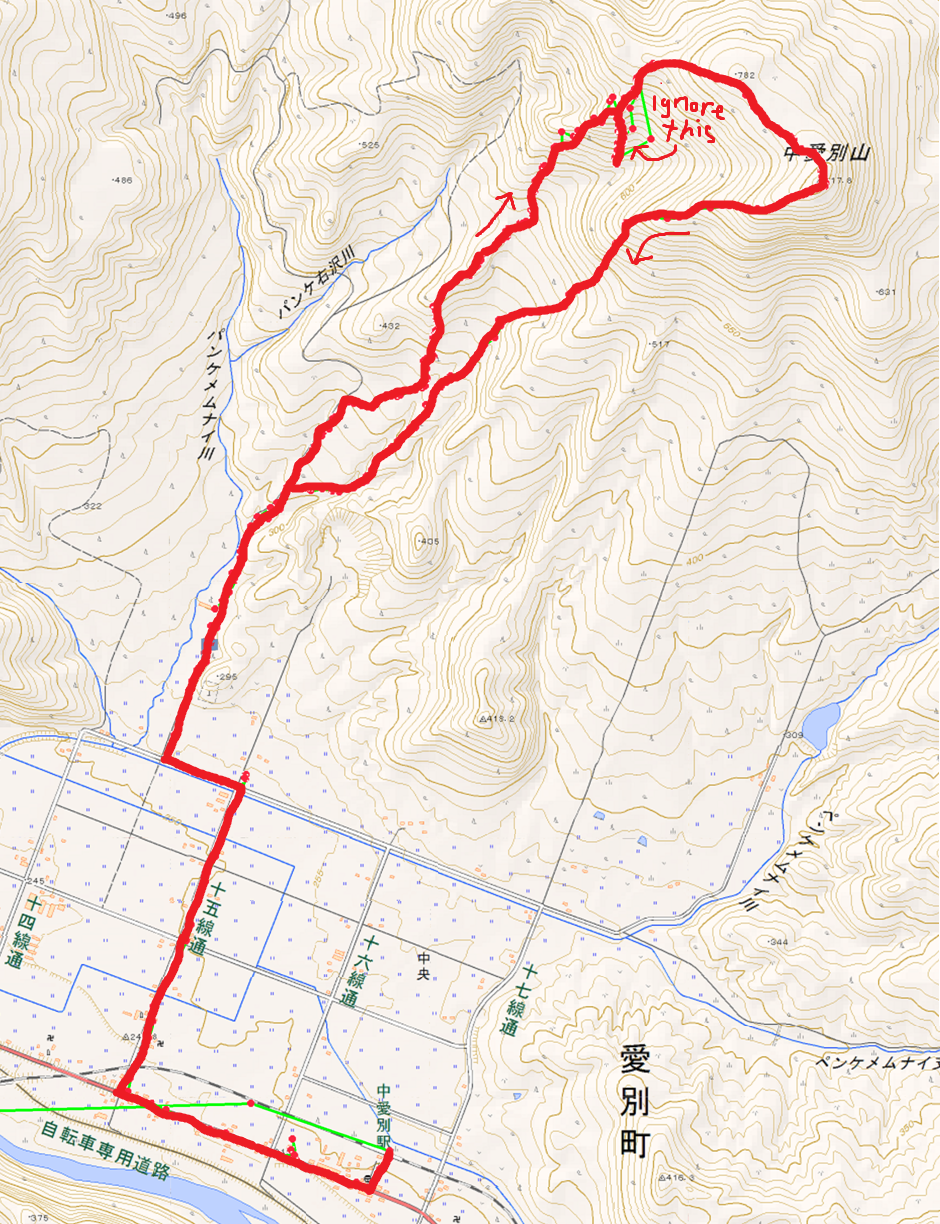

I weighed the virtues and difficulties of mountains around Asahikawa (like price of train ticket, length of hike, distance between trailhead and train station, etc). I used a bunch of resources, like Google Maps, the GSI (Geospatial Information Authority of Japan) maps, Japanese hiking blogs (super useful places with a ton of nifty information and data about hikes), as well as train as bus schedules. Eventually I decided that Nakaaibetsu-yama (中愛別山, 817.8 m) suited all of the requirements I had and set out making a solid plan. And there you have it. TA-DAA I was on my way to zapping my midweek boredom by hiking… sans car! It can be done!

Getting down to business

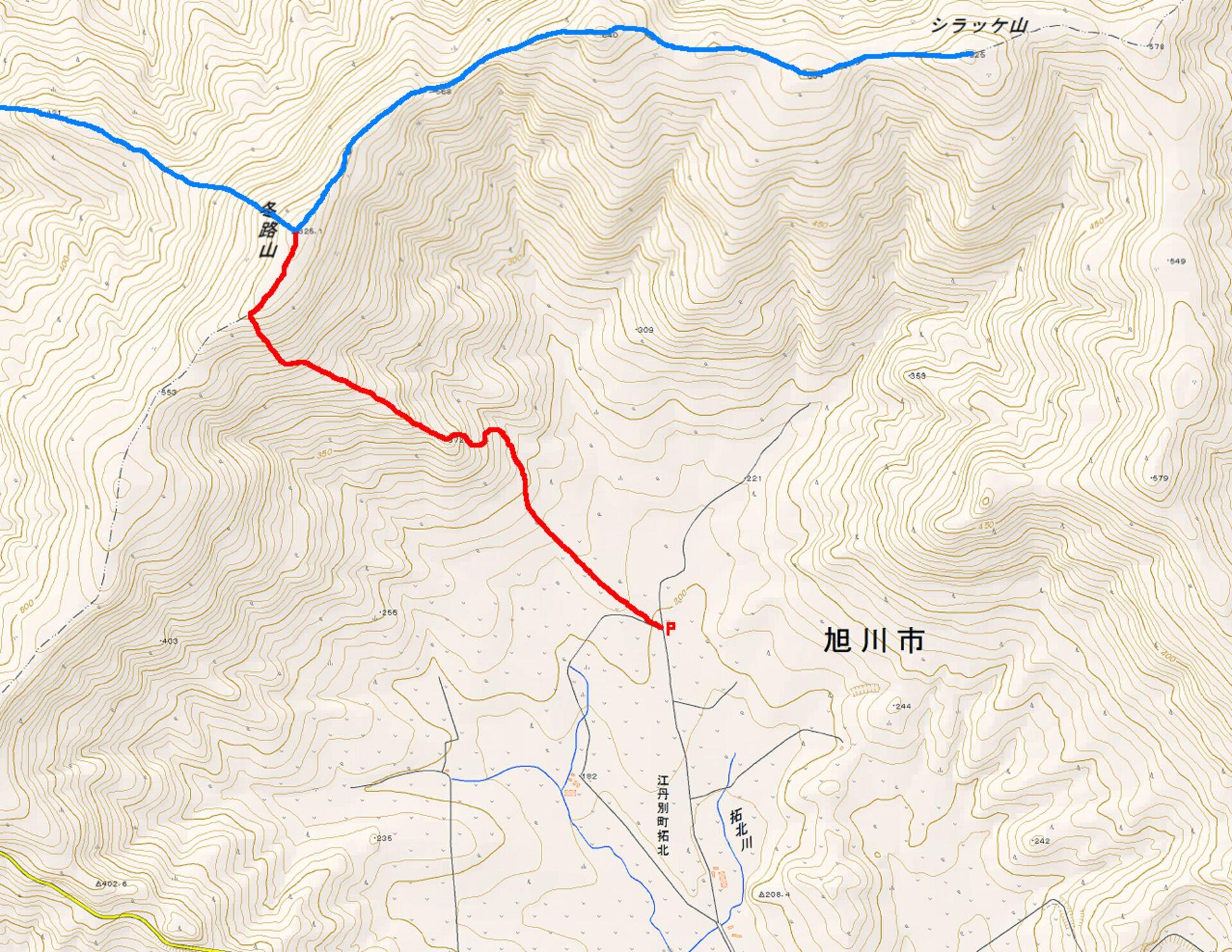

The trail itself starts about 2 km away from Nakaaibetsu Train Station. It follows a forest road which is ploughed only a very short way until you reach some kind of industrial site. I put on my snowshoes once I hit the unploughed forest road and followed the road for about 1 km. I was also following the trail of a skier. He left the forest road where I did as well so that gave me confidence that I knew where I was going.

Walking through a forest area I continued with the skier but soon it appeared clear he was going a different path down through a wee valley, so that’s where I said goodbye to my leader and decided that Fleetwood Mac circa 1976 got it right, and I started singing “Go Your Own Way” loudly and proudly.

Next came a steep(-ish) part, but it didn’t last long; and I guess in summer there’s a hiking trail there, because that’s where I saw my first pink ribbon. It flattened out for a second and then I did another wee climb. Nothing too dramatic.

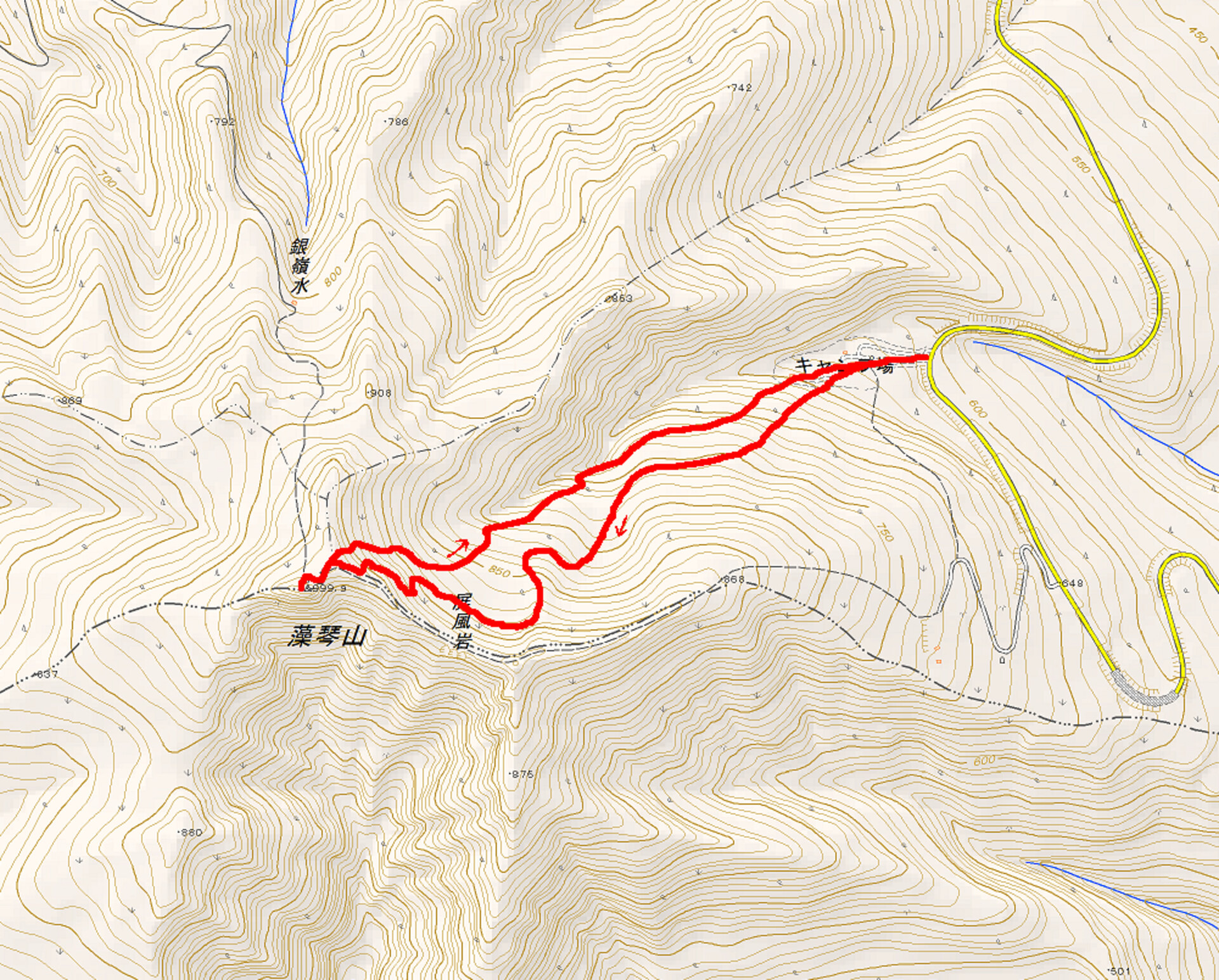

Walking along the ridgeline at the top of that part was lovely. I had my first views of both sides and it was almost flat so it was a nice break. However, it didn’t last so long. I was lured into a lovely, warm feeling of accomplishment and confidence like, well, that wasn’t hard. Silly me.

The next section was where it really got fun. It got steep and hard to follow because it was very foresty. I found it difficult to keep to the ridgeline. Unfortunately, my stupid GPS was being stupid and I definitely, definitely didn’t go the most efficient way. That wasted a lot of energy. But I made it. Eventually.

Once I got to the top of the steep bit it was a piece of cake. It was also completely beautiful. The trees were like from movies where the wintertime is given a magical-type feel and it was peaceful and quiet. Walking through the magic trees, the incline was so slight compared to the previous steep section I hardly noticed it at all; and I had the sight of the summit the whole way, so morale was high and I couldn’t wait to make it.

The views from the top were lovely. I was promised better weather but it was good enough. I could see the shapes of the mountain ranges around me that I recognised from spending so many hours staring at Google Maps. Nothing will ever compare to seeing the real thing. I can see a million pictures of mountains, old famous ruins, the countryside from back home, but no number of pictures can bring me the feelings that I get when I see the real thing with my own eyes.

I’m a curious being and I also get bored really easily so the decision to take a different route back down was easy. Didn’t really feel like a decision even. I made short work of it. I chose a steeper route and practically skied down on my snowshoes. I completely love going down mountains. Up… not so much if I’m honest. But the joy I get from the bounce down the mountain is almost always worth the trudge up it.

Towards the bottom of the mountain I met back up with my former leader’s trail and found my way back to the forest road and I was home and dry. I had to wait a while for the next train but that’s cool because I’m a smart little one and I brought entertainment.

So, Nakaaibetsu-yama is a totally cool mountain, folks. Steep at times but worth it because if there’s good weather, there’s a really good opportunity for stunning views of Asahikawa and the Daisetsuzan.

Today I learned

In true TIL fashion, I learned barely any of these today:

- No matter what anyone tells you, Hokkaido wildlife are some of the best hikers in the world. Those little critters took the best lines.

- I’m a sheep. I followed the little rascals’ paths all the way to the top. They were following ridgelines like they’d taken pro-level mountaineering courses.

- Animals are scarce in the Hokkaido winter. Or at least, you scarcely see them. I saw two living beings: a crow bro and a spider bro.

- Skiing down Nakaaibetsu-yama doesn’t seem like the most fun. Forest is super dense and you’d have to skin back up after like 30 seconds of skiing. Boo.

- Don’t trust weathermen. They said it’d be a blue sky all day. Was it balls.

trailhead: 10:40 -> summit 13:40-13:50 -> trailhead 14:50

climbing time: 3 hours / descending time: 1 hour